18_The Chord Progression of Wealth Management: Unrealized gains, the Tax-Code, and Step-Up in Basis

How the Wealthy Use the Tax Code to Maximize After-Tax Growth

A lot of what I do involves understanding the key principles of financial planning and being able to combine these in ways that result in creative solutions to complex problems.

It’s the creative composition of first principles that reminds me of the time my hands started improvising playing the piano without my brain previously thinking about the notes that needed to be played beforehand.

So I thought I’d convey that story here, because it ties into one of the main tenets of this Substack.

Namely, as with all things education, it’s not what you learn that is the long-term value proposition.

What you learn is the short-term value add.

The long-term value proposition is how learning those things allow you to engage with the world around you from a different perspective and create new solutions to problems you weren’t even aware existed prior to learning that information.

That’s what you take with you forever—long after you forget about the individual thing you learned.

And that is ultimately, what I’m hoping you take from this Substack; not the boring details and principles of finance and insurance—but how if you take a deeper look at the world we live in, you’ll find a plethora of ways that the already wealthy are allowed to amass even more wealth with both reduced risk and reduced taxation simply because they understand how to use tools that most people don’t even know exist or even have access to.

Understanding Chord Progressions

I took a year off between my first and second year of college and when I returned to college I was looking for a means of personal expression.

It just so happened that the college I went to was an expensive one and had one of those extravagant grand pianos in the dorm living room that largely went unused.

So playing the piano seemed to be a perfect fit.

I settled on playing two classical songs that I found really moving: Moonlight Sonata and Pachelbel’s Canon in D.

The problem was that I didn’t play the piano and couldn’t read music.

So I spent dozens of hours memorizing one note at a time until I could play the whole song.

And then I spent dozens of more hours playing the song until it felt more natural and less rehearsed.

And then a crazy thing happened after spending like a hundred hours playing just two songs.

My hands would start to experiment with the notes.

So my left hand would play the memorized portion and my right hand would start searching for keys that would mesh with what the left hand was doing.

But the crazy thing is it’s not like my brain knew what my hand was doing because I could neither read nor play music by ear.

My right hand just seemed to be instinctively searching for something that it knew went well with the melody—independent of me thinking about it.

It was a freaky experience to have your hand operate seemingly independent from your brain.

At the time I had no explanation for what was happening and so it was a surreal out of body type moment to watch my hand play keys without any idea of how it was doing it.

I know now that what my right hand was doing was essentially playing chord progressions based on whatever the left hand was doing.

But at that time I had know idea what a chord was.

To be honest, even now I can’t really tell you what the different chords are.

I just know that at the end of a couple hundred hours my hands were playing melodies that I had not memorized and had never played or even thought of before until I sat down at that very moment to play whatever my hands wanted to that day.

It was a magical experience for someone whose hands had only ever known basketballs that transmitted dirt from playgrounds to my fingers or callouses on my palms from gripping weights too tightly at the gym.

The finely crafted black and white keys on a Yamaha grand piano were worlds away from that.

And here I was seemingly improvising on them like I knew what I was doing.

Understanding the Key Notes of Wealth Management

You’re probably wondering what all this has to do with financial planning, unrealized gains, tax laws, and step-up in basis.

Well I’m getting there.

My hands haven’t touched a piano or keyboard in years, but I have spent nearly every day for the last 12 years thinking of some nuanced rabbit hole of personal finance that derives directly from the value of either unrealized gains, the tax code, and step-up in basis.

And if I only had 1 sentence of personal finance wisdom to get across to people it is to understand the value of unrealized gains, the tax code, and step-up in basis.

Unrealized gains, the tax-code, and step-up in basis are like the Pachelbel notes I was trying to memorize.

They form the major notes of any strong wealth management strategy.

Once you understand these notes then you can combine them in a myriad of ways to craft solutions to complex problems.

But it all starts with mastering these notes to begin with.

For those who don’t know what unrealized gains are, they are the price appreciation of any equity position you hold (e.g. the increase in the stock or the S&P 500 fund you own).

This price appreciation is not taxed until you sell it.

For example, if I purchase a $1,000 of Apple stock and it goes to $101,000 I am not taxed on that gain. That gain is referred to as an “unrealized” gain because I have not sold the stock and “realized” the gain.

On the other hand, if I sell the stock for $101,000 then I have a $100,000 realized gain over what I purchased it for ($101,000 - $1,000 = $100,000). The $1,000 price that I purchased it for is also known as the stock’s “cost basis”.

And then I have to pay federal and state taxes on that $100,000 gain.

And the amount of tax I pay depends on both how long I held the position before selling as well as the amount of other income I make.

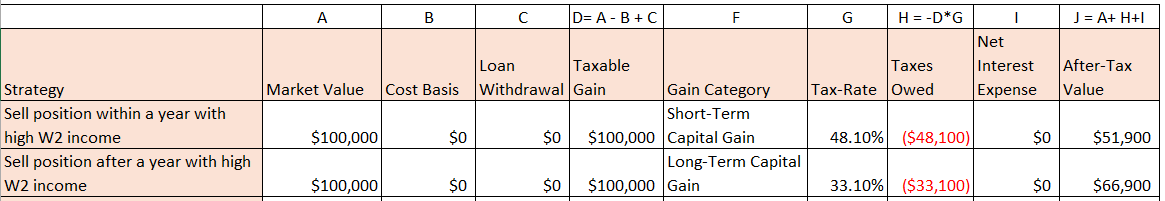

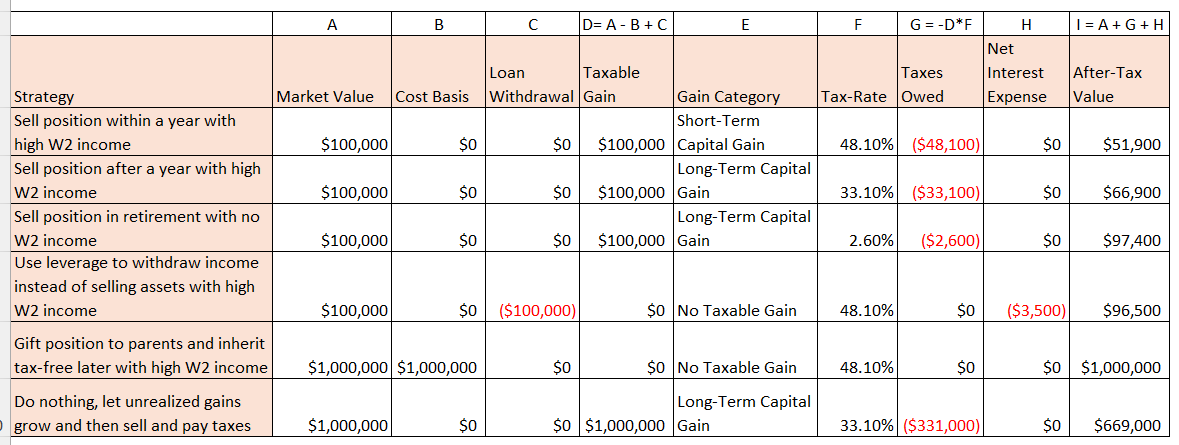

Let’s take a married couple client who make $600k/year in W2 income, and lives in California as an example—which means they are in high marginal tax brackets.

Short-Term Capital Gain vs Long-Term Capital Gain

If the client has a $100,000 gain on selling that Apple stock and the client held it for exactly one year (classified as a short-term capital gain), then the client is losing 48.1% or $48,100 of that to taxes (35% federal, 9.3% state, and 3.8% NII).

That leaves them with only $51,900.

What if they waited just one more day to sell the stock?

Well then the stock would qualify as a long-term capital gain and they would only lose 33.1% to taxes (20% federal tax, 9.3% state, and 3.8% NII).

This would leave them with only $66,900.

So making a simple choice to hold a stock position one more day can increase the client’s after-tax return by 28.9% ($66,900/$51,900) without significantly more risk.

Short-Term Tax vs Long-Term Tax Rates on Realized Capital Gains

The Value of Tax Deferral Until Retirement to Benefit From Lower Tax Brackets

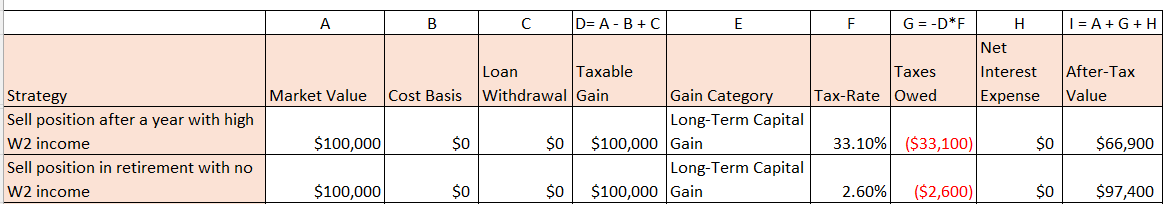

However, you might be looking at the 33%-48% tax rates I just mentioned for the client and wondering why those are so high.

And that’s because the client is already making $600k/year in W2 income.

So any additional income they earn in that year gets taxed at higher rates than if they weren’t making any W2 income in that calendar year.

Well that might lead you to ask the question:

What if the client retires and so has no W2 income in that year?

How would that affect the tax-rate on that gain?

Well in that case they would only have $100k of long-term capital gains. They would pay 0% in federal taxes (since they are benefitting from the 0% long-term capital gains tax rate up to ~$126,700k in income).

They wouldn’t pay the NII since their income from the year is low. On the state side they would only pay $2,600 in state income tax since they are a married couple with only $100k in taxable income.

So that means on their entire $100k in income they are only losing $2,600 of it to taxes.

Which means they get to keep $97,400 of it—or 97.4%.

That’s an 88% increase ($97,400/$51,900) over what they would have kept if they just had a $100k short-term capital gain while making a high W2 income.

So with proper planning, clients can defer selling their positions until they no longer have W2 income (i.e. retirement) and then benefit from the significantly lower tax-liabilities.

Deferring Realized Capital Gain Until Retirement with No W2 income

Using Leverage Against Your Portfolio

While that sounds phenomenal, the client might then say to me,

“Rajiv, only paying long-term capital gains rate when I retire sounds great! But what if I need to sell some of my portfolio today? What if I need income now?”

To which I would say,

“Have you looked at borrowing against your portfolio?”

Most people don’t realize that you can borrow against your portfolio in a similar way to how you can get a second mortgage on your home if you want to capture some of the equity that’s built up.

The added benefit here is that if you do it effectively, you may never have to actually pay that interest back while you are alive (unlike a second mortgage in which you are actively paying off the principal and interest every year).

That way instead of selling an asset making ~10% and losing out on the future gains, you can borrow against it at around 4%-7% without ever having to pay it back. Plus the interest on that is deductible. So if you’re borrowing at 5% at a 30% tax-bracket, that’s really only a net cost of 3.5% (5%-0.3*5%=3.5%).

So if we take $100k loan against our portfolio at a net cost of 3.5%, the net cost of the interest for each year is only $3,500. Which means you’re keeping $96,500 AND that $96,500 is still compounding and earning returns going forward in the market (as long as market returns are above the rate you’re borrowing at).

In essence, clients are using the benefits of leverage here the same way they would with refinancing their house. The client is keeping 96.5% of their gain and still earning returns going forward on the difference between the appreciation rate on their asset (in this case their portfolio instead of their home) and the net leverage rate.

Borrowing Against Your Portfolio Now Vs Selling in Retirement

The leverage here is accomplishing three key goals here:

1) Allowing clients ability to access their profits immediately instead of waiting until retirement or paying 20%-30% in capital gains tax due to their high W2 income

2) Allowing clients the ability to profit going forward off the difference between their net leverage rate and the rate of return that the portfolio is making

3) The ability to never pay taxes on the gains due to step-up in basis (as described below) all while continuing to access the liquidity via future loans.

Step-up in basis and tax-free generational wealth

You might also say to me,

“Rajiv, what if I don’t want to use leverage AND expect my tax rate in retirement to be just as high as it is today?”

To which I would say:

“Are you familiar with gifting strategies and step-up in basis?”

If you gift the stocks to your elderly parents, then they pass-away you would inherit those gains tax-free.

So let’s say you gave those stocks with a $100k unrealized gain to your parents.

This is not a taxable event to either party (unless you’ve already gifted $14M in assets already). You are merely making a gift to another party who is accepting the gift. The gift will only be taxable to them if they sell the asset—which they don’t plan on doing.

In 20 years, when you’re ready to retire let’s assume that gain has grown to $1 million.

When your parents pass away you would inherit all those gains tax-free due to step-up in basis.

That’s because prior to death the cost basis on those gains were $0.

But when your parents pass-away, that basis is “stepped-up” to $1 million and the assets are given to you.

So now you can sell the assets with $0 taxable gain ($1 million value -$1 million cost basis =$0 taxable gain).

That means you get to keep the full $1 million.

This tax strategy is known as upstream gifting.

However, if you had kept those assets yourself, then there would be a million dollar taxable gain ($1 million value - $0 basis =$1 million taxable gain) since the basis is not stepped up if you own the assets and then sell it. At a 30% tax rate, that would be a loss of $300,000.

Inheriting Assets Tax-Free vs Selling Them and Paying Taxes

So simple financial planning would allow you to essentially make the growth of your asset fully tax-free.

Keep in mind you were already saving for a retirement that was 20+ years away which was around the time you would have expected your parents to pass away.

It’s worth noting that wealthy families use this step-up in basis concept to pass on wealth tax-free from generation to generation.

And to the extent that families need income during their current lifetimes, instead of selling those assets, paying taxes on it, and losing on the opportunity cost of future growth, families can just borrow against their assets like I mentioned in the previous section, receive the tax-deduction for doing so, and have those assets and large unrealized gains pass to the next generation tax-free.

It's a cheat code for the wealthy and financial planning community that very few fully utilize—even though it’s technically available for all to do (it’s just that the wealthy benefit the most because of their high tax rates and the fact that they have people educating them on it).

Wealth Management Chord Progressions

There are a thousand different ways you can combine these key notes of unrealized gains, the tax-code, and step-up in basis to address individual client problems.

This involves maximizing the use of qualified and non-qualified retirement plans, asset location strategies, moving assets outside of the estate through estate planning, utilizing discounted valuation practices to reduce taxation on Roth conversions, QSBS and opportunity zone investing, tax-free exit planning for business owners, and many more.

All these really are though are just chord-progressions of those 3 key notes—just utilized in a way that takes the legal precedent they set and combines them in such a way that addresses a whole host of financial planning issues outside of what they were originally intended to provide.

But in order to understand these progressions, you need to understand the foundational notes on which they rest.

So if I were to make recommendations to anyone studying wealth management for yourself or others it would be to really study the value of unrealized gains in your portfolio, the tax-code and step-up in basis.

Doing so will likely result in millions more that are passed from one generation to the next in the form of more compounded growth, reduced taxation, and increased risk-management strategies.

But the unfortunate reality is that most people don’t think about any of the financial planning opportunities that I mentioned in this article.

Instead they let that $100k unrealized gain grow to $1,000,000 and then when they need the money they sell the whole position and lose $300k+ to taxes when they could have accomplished their same goals and need for liquidity without absorbing the $300k loss.

The possibilities for using the tax-code and financial planning are endless.

The Value of Understanding the Tax Code and Financial Planning

But it requires you to first spend the time understanding these 3 basic notes to begin with.

About the Author

Rajiv Rebello is the Principal and Chief Actuary of Colva Insurance Services and Guaranteed Annuity Experts. He helps HNW clients implement better after-tax, risk-adjusted wealth and estate solutions through the use of strategic planning and life insurance and annuity vehicles. He can be reached at rajiv.rebello@colvaservices.com.

You can also book a call directly with him here: