Are You Really Investing in a Better Life—or Merely Speculating on the Value of a Future Outcome?

Understanding the difference between investing in a better life for ourselves versus speculating on the value a future outcome might provide can help prevent us from losing who we are in the process.

The American Dream has always consisted of an idealized vision of a nice home, expensive car, luxury vacations, and a perfect family to boot. We’re told that if we work hard enough we can get all of these things—and that we should aspire to want all of them. That these are all absolute goods and not relative ones.

It is a view of life that seeks to foster a sense of ambition and a feeling of purpose that comes with achieving a goal that our ambition made reality.

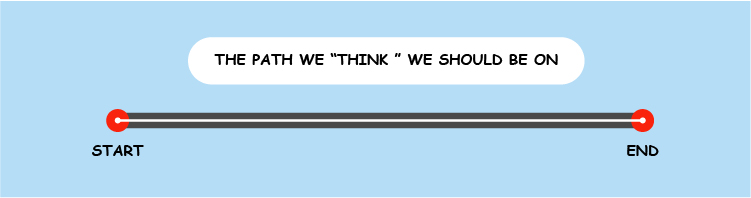

But more often than not, it’s the path we take towards obtaining our goals that derives this feeling of purpose for us and not the outcome. The outcome isn’t nearly as important as the path we’re on—and how that path aligns with our view of the world.

We can get the outcome we wanted, but if we didn’t enjoy the path we took to get there then the value we receive from the reward might seem small relative to what we had to give up to get it.

So the problem with this view of the American Dream is that we are selling everyone on the upsides of ambition without fully disclosing the risks.

If I did this as an investment professional, this would be malpractice.

With investing we view risk in terms of money that we could lose. The more money we can lose, the more risk involved with that investment.

However, we invest a lot more than just money in our daily lives. Every choice we make comes with a cost to our time, energy, and emotional bandwidth. And if we invest these poorly, we can risk losing the very essence of who we are.

So the stakes here are high. Especially since we often overestimate the value we think achievement of the goal can bring to our lives and underestimate the risk involved in pursuing it. This is an element of human psychology called loss aversion in which people have been shown to experience the pain of loss more than the joy of gain, even if the amount of the loss and the gain is equivalent.

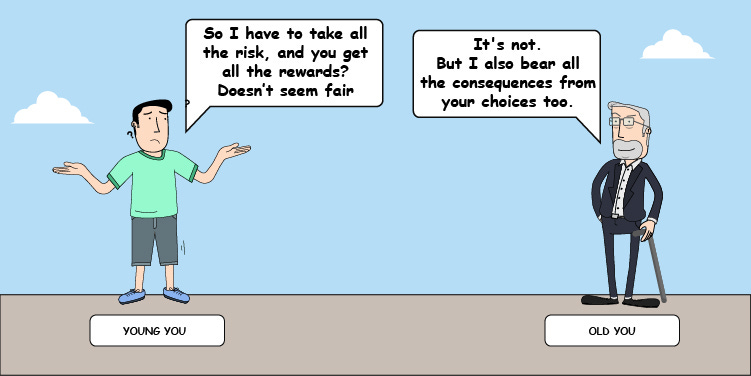

This is because it is our current selves that takes all the risk and makes the initial investment, but it is our future selves who will reap all of the rewards—and bear all of the consequences. And these two people don’t always value things the same.

As any investment professional knows, trying to project future returns and value with any level of confidence is extremely difficult. But paying an immediate upfront price now is known.

So the risk we forget to take into consideration here isn’t the possibility that we don’t reach our goal; it’s the possibility that even if we reach our goal we may be investing a huge part of who we are today in pursuit of something that doesn’t even matter anymore to the person we are in the future who actually achieves it.

Return on Investment vs Risk (Volatility)

In finance we use metrics to measure both return and risk. Since I’m a numbers guy, I find it easier to help utilize these metrics in the decision making process. While all metrics have their flaws—some of which I’ll be touching on here—they are helpful in understanding the concepts we’ve been talking about here and the overall direction we should be headed in.

The two metrics I’ll be discussing are:

1) Return on Investment (ROI) and

2) Volatility—which is just a measure of risk.

I will be simplifying the calculations of these metrics so we can focus on the concepts here and not the actual calculation.

One of the most important metrics we consider is known as Return On Investment (ROI). Both parts of the exchange are measured in currency. The investment we give to others is our money. We earn a return on this investment from the work of other people. We’re always hoping that the return we get back is larger than the investment we put in. So if we invest $100 of our own money, we’re hoping we get at least $100 back.

We can use metrics like ROI to determine how good of an investment we made based on the difference between the amount of money we invested versus what we received back. So if I invest $100 in two investments and receive $100 back from the first one and $300 from the second one, then the second investment had a greater ROI than the first.

The problem with ROI is that it only focuses on what you invested at the beginning and what you received at the end—without accounting for the value of the path you took to get there. For example, let’s say you have $100 and can invest in one of the two following investment opportunities:

Risky Investment: At the end of the year you have a 50% chance of receiving $300 and a 50% chance of ending up with $0. The expected return here is $150 (50%*$300 + 50%*$0).

Safe Investment: At the end of the year you have a 50% chance of receiving $151 and a 50% chance of ending up with $149. The expected return here is $150 (50%*$151 + 50%*$149).

In both cases the expected return is $150. But the journey to the $150 is entirely different. With the Risky Investment, in the best case you triple your money and in the worst case you lose everything. That’s a path filled with enormous highs and enormous lows. In finance we refer to this as volatility. So this investment would have a lot of volatility.

We can think of volatility as a measure of how far away the path takes us away from our expected return—or the center of where we expect to be. If the center is $150 and our path can take us $150 away from this center in either direction, then the volatility here is $150. The risk here is that the path takes us $150 away from where we expected to be.

With the safe investment, in the worst case you end up with $149 and the best case you end up with $151. This investment has low volatility. This investment has the lowest risk. In terms of volatility, the path only takes us $1 away from where we expect to be in either direction.

If we think of this purely from a return vs risk standpoint, the Safe Investment is the better option. It minimizes how far away the path can take us from our expected center of $150. In finance we call that maximizing the risk-adjusted return because we maximize the return relative to the risk we are taking.

But in real life, the Safe Investment isn’t for everyone. There are a number of reasons for this:

1) Return on Investment (ROI) is not the same as value:

Return on Investment is an objective metric of finance. We use certain formulas to calculate a return objectively. This calculation is the same for everyone.

Determination of value is a subjective assessment dependent on the individual who is receiving the return. This determination is often different for each person. Two different people can receive the same return, but value that return in completely opposite ways (as we’ll see in our next example). Value is a function of our own perspective—not of return.

It’s for this reason that we distinguish broader “finance” from “personal finance”. Personal finance is inherently personal and has less to do with numbers as it does with the value systems of the individual people making the decision and how that decision makes them feel.

2) In finance, return and risk can be thought of separately. But not when assessing value:

In the above example we calculated the return on investment for each option and then we calculated risk by determining how far each investment risked taking us away from where we expected to be. As we saw in the above example, you can have the same return with two very different risks—one large and one small.

However, we can’t say the same when we compare value and risk. Value and risk are correlated. We just measure risk differently when we are trying to assess personal value as opposed to financial return. When we calculate return on investment, we define risk as how far away from our expected return that investment can take us. However, when we determine the value that an outcome has to us, we consider how much our lives can benefit or be hurt from the outcomes of the decision. It’s an inherently personal and subjective determination. The farther away that outcome can take us away from who we are and what we value, the less valuable it inherently is—and the more risk it poses.

It’s easier to understand this by looking at an actual example.

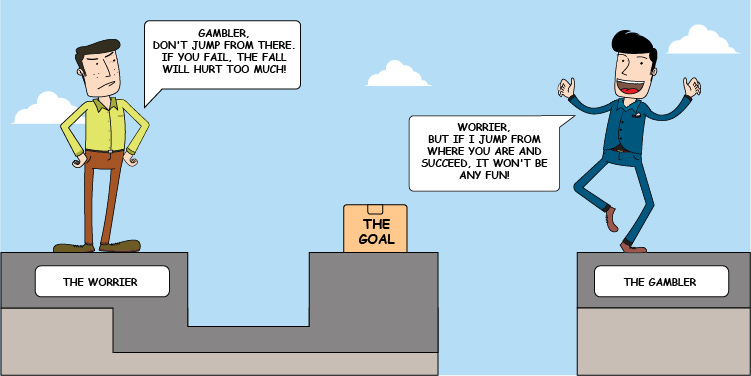

The Gambler vs The Worrier

We all know people that would choose the Risky Investment over the Safe Investment. Let’s call this person the “Gambler”. At their heart, the Gambler is all about taking chances with life and unplanned adventures. They live life on the edge—and prefer it that way. They find joy in the highs and can move on from the lows in a way that others cannot. So the Risky Investment might be the right personal choice for them, even though it was the worst of the two investment options. That investment style is the best fit for their values—even though it comes with significantly more risk.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is the “Worrier”. The Worrier is constantly focused on trying to do the “right” thing—and not doing the “wrong” thing. The safe investment is the best option for the Worrier. At the end of the year, he or she gets an almost $150 guaranteed return. They spend the entire year feeling proud of themselves knowing that they’re coming out ahead either way, and whether they get $149 or $151 doesn’t matter nearly as much as the pride they feel about their choice.

Now imagine we forced each party to invest in the investment option that was antithetical to their value system. The Gambler was forced to choose the Safe Investment, waited a year not knowing what the result would be, and at the end of the year receives $151—the best case scenario given that option. The Worrier is forced to choose the Risky Investment not knowing what the result would be, and at the end of the year receives $300—the best case scenario for that option.

The value that each receives from receiving the best case scenario of the investment option that is a bad fit for them is actually worse than the value they would receive from the worst case scenario of the option that was the best fit for them. To understand why, it’s important to examine the psychology behind it.

For the Gambler, the Safe Investment doesn’t provide the excitement of anticipation that comes with waiting to find out if they’ve won or lost. The excitement is what provides value to their life—not the outcome. Even if they lose their money with the Risky Investment at the end of the year, they still get to spend that year up to that point anticipating the outcome. The value for them is in the anticipation. The Safe Investment just provides them with an almost guaranteed $150. The path to that guaranteed outcome is boring to them—and in a lot of ways invalidates their way of living. If they believed in taking the safe and guaranteed outcome, they wouldn’t have chosen to live their lives in the way that they do. They wouldn’t be the “Gambler.”

So with the Safe Investment, the Gambler loses the excitement that would be provided to them over the course of the year of waiting to see the outcome. Instead, they are largely apathetic to the outcome since they know the end result in advance is more or less guaranteed (there is minimal difference between receiving $149 vs $151). They’ve essentially replaced a year filled with excited anticipation for a year of apathy. And as soon as they get the $151 they would immediately gamble that $151 on another risky investment that gives them the excitement that they were actually looking for in the first place. The money is just a means to provide excitement and value to their lives. In the absence of this excitement, there is no value to the money.

For the Worrier, the Risky Investment forces them to endure a year of anxiety wondering if they are about to lose their entire investment. Even at the end of the year when they get the $300 they don’t feel the joy that the Gambler would experience from winning $300. Instead, they feel relief that they didn’t lose $100. The positive outcome they received at the end wasn’t enough to outweigh the fear the Worrier experienced in the interim.

The point here being that for both parties, the value each party receives from investment isn’t in the return—even though both parties receive the best possible return given the investment option. It’s a problem about money that actually isn’t about money. It’s not what we receive in the end that matters; it’s about how we experienced getting there and how that experience aligns with our view of the world and our values. And most importantly, how far that path took us away from who we are or the person we expected to be.

In fact, the Worrier would take much less in guaranteed money than take the risk of losing it—even if on average they would be mathematically better off taking the risk. So if the Safe Investment only offered a guaranteed $110, the Worrier would probably still take the Safe Investment even though on average the Risky Investment would offer $150—albeit with significantly more risk. In finance we call this being risk-averse.

Now there is a conversation to be had about whether basing a life centered on safety and fear of risk is as objectively enjoyable as one based on the excitement that comes with significant risk but the chance for better outcomes, but that deserves an entire post on its own.

The point I want to focus here is how choosing to go down a path that is not in alignment with who we are can invalidate the outcome for us here—even if the outcome is objectively positive. It’s a play on the “Do the ends justify the means?” dilemma but evaluated not from a moral/social perspective, but from a deeply personal desire to find and give meaning to our lives.

The idea of being a world famous plastic surgeon may sound appealing on the surface when we look at the lifestyles some of the world’s most famous plastic surgeons live. But are we willing to put in 19+ years of schooling constantly pushing ourselves to get the best grades, and get the best positions to get there while giving up the bulk of our 20s? Are we willing to surround ourselves with other hyper-competitive individuals striving to do the same thing? Is that the environment we want to live in and be a part of?

For the Gambler it definitely isn’t. Perhaps for the Worrier it might be as the Worrier is more willing to sacrifice current joy for later stability. But then again, is it really healthy to put the Worrier in a position that imposes more stress and worry on his or her life when stress and worry already preoccupies his or her life? That’s a question I hope the Worrier would deeply consider before pursuing that path.

We live in a time of glorifying “hustle culture” or the concept that if we work hard enough, we can achieve anything. But we rarely stop to ask ourselves if the path to achieving everything we thought we wanted was worth losing who we are in the process. Because the risk here isn’t just failing to achieve the outcome we wanted; it’s also achieving everything we thought we wanted at the beginning and along the way turning into someone who can’t find joy or peace in everything we worked so hard to achieve at the end. The person we become at the end of the journey may not be the same one who started it.

Every decision we make today for the future is a choice to sacrifice the current moment for an unknown outcome in the future. The question we often fail to ask ourselves when we do this is if we are truly investing today’s experiences for a better future experience of life or if we are just gambling the moment away based on unrealistic speculation of the value we think our future selves will receive from the accomplishment.

The sad part of life is that sometimes it’s the Worrier doing the speculating while thinking he or she is investing when it’s actually the Gambler who is investing in a better experience of life for him or herself by taking large risks.

The duty of a financial advisor isn’t to convince the Worrier to be the Gambler or vice versa. The job is to make sure that each party is fully aware of the risks at hand so that they can make the best decision based on who they are. In order to do this, we need to understand the value system and personality of each client on a very deep level. Only by doing this are we able to assess whether the client is actually investing or just gambling.

Unfortunately, many of us mistake the “right” path as one that is focused on a singular outcome, eg the “path” to be a CEO or the “path” to be married with children. But these are all focused on the end result and we see the road to getting there as a straight line. There’s a start point, and an endpoint, and a straight line to get there.

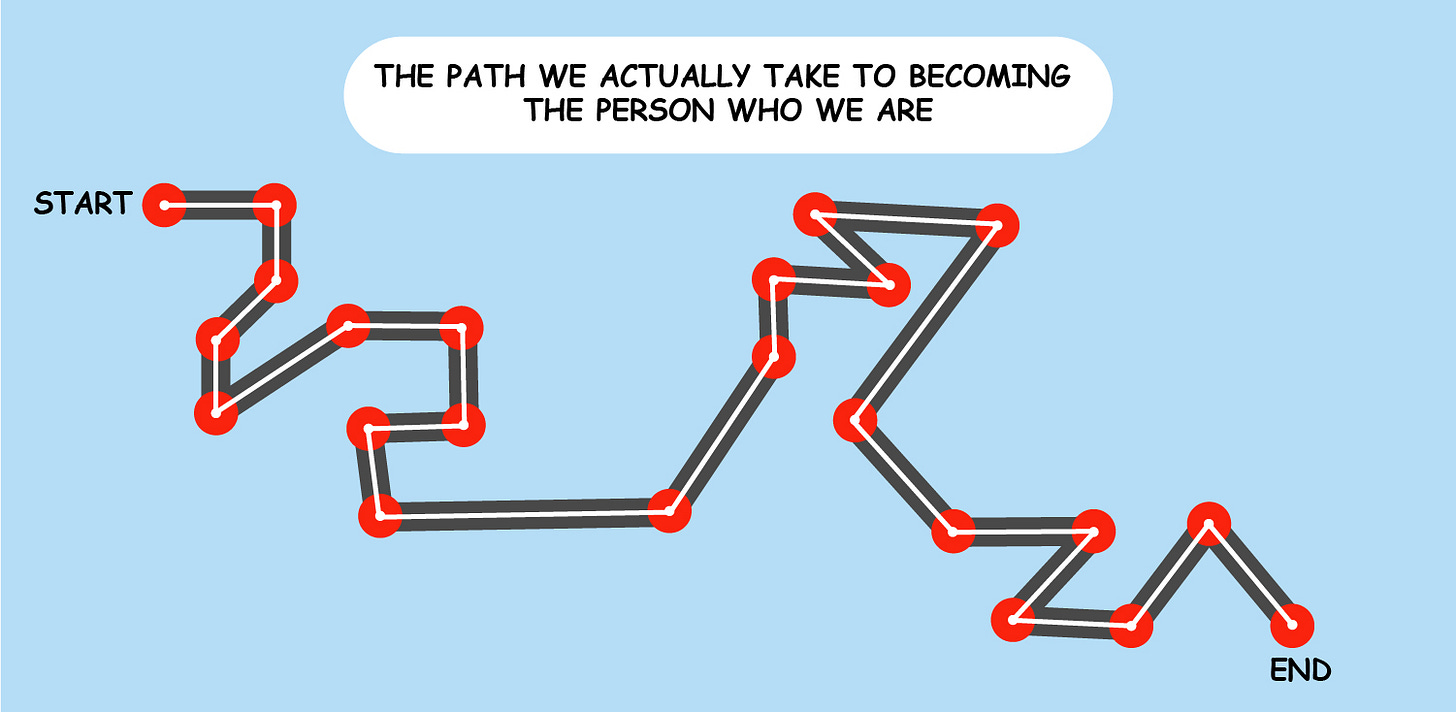

However, the path of our lives isn’t one linear road with a singular start and end point. It is a cumulation of start and end points. Sometimes it’s circumstance that brings us to the next point (eg, being laid off at work or graduating from high school), sometimes it’s choice (eg, taking a new job in a new city or buying a house) and other times it’s a combination of both. Sometimes the point takes us forward, other times it takes us backward, and sometimes it takes us in a direction we never anticipated going in at all.

The way we maximize the value our lives bring us is by trying to focus on how our choices at each point (the only part of our lives we have control over) can bring us closer to the center of who we are and want to be. Resentment builds when our path brings us away from this. Taking steps towards bringing us closer to who we want to be helps alleviate this resentment. By focusing on the person we want to be instead of a specific outcome we want, we acknowledge that our journey is about developing ourselves and not running after things.

Unfortunately, not all of us have the privilege of trying to choose the path that best fits us—we’re too busy just trying to survive the path we’re currently on. The ability to pursue more agency and personal fulfillment in our lives is not freely available to everyone. But for those of us who do have this privilege, these are concepts worth examining.

After all, in the end, the final outcome/endpoint for all of us is death. If we spend all our time chasing after our ambitions, we run the risk of reaching the final destination before we had time to actually enjoy the fruits of our labor. But focusing on our path and how that aligns with who we are in the moment and the person we want to be in the future—instead of the idealized outcome we want in the end—allows our sense of meaning and purpose to come from a constant exploration of self and who we are and the agency of our actions in the midst of both controllable and uncontrollable events.

It allows for grace, and forgiveness, and it allows for the path to change directions as we do. We stop focusing on trying to change ourselves to fit a pre-determined path meant for other people, but on the search to mold the path we’re currently on to best fit who we are as individuals. It allows us a means to balance out the pain that comes from looking back at our past, comparing it to where we are today, and saying “I’m not where I thought I would be” with the peace that comes from looking towards our future and completing that sentence by adding the more important qualifying clause, “but I’m moving closer towards who I want to be”.

When we are able to do this, we are able to value those moments in which our path fits our calling, and try and change the trajectory of that path as our sense of self diverges from it. It’s an inward exploration of what it means to be free versus an outward exploration of what outcomes we can achieve. It puts the emphasis on the direction we want to head in—not the place we want to arrive at.

If you risk who you are for an outcome and you fail, you’re left with an experience you didn’t want to have and an outcome you wanted even less. But if you try and become the person you want to be and never completely get there, the person you did turn into is still someone you’re more proud of being than the person you are today. And the journey to becoming that person is one that enriched your experience of life along the way by teaching you not only more about yourself, who you are, and what you truly want out of life, but also about the world you live in.

And if by chance you find yourself far removed from the path towards who you feel you truly are and want to be, know that there is still hope for you. If you’re able to work your way past the pain of your situation, there’s a beauty to be found amidst your struggle to find your way back. So I’m wishing you well.